Lp(a) is very similar to LDL-c, except that it has a “tail” of protein called apo(a).

Each segment of the tail is called a kringle (since it resembles the Danish pastry), and how many of these segments an Lp(a) particle has is called kringle repeats.

Lp(a) is sometimes referred to as the “sticky” cholesterol, probably because of the kringle tail’s ability to intertwine with other Lp(a) particle tails.

Lp(a) is rare to find across animal species. As far as we know, only two have it: primates and hedgehogs. Why is this so rare? Dr. Linus Pauling (a double Nobel prize winner) theorized it has to do with our inability to make vitamin C (only humans, fruit bats, gorillas, and guinea pigs cannot make their own vitamin C). One of the functions of vitamin C (in conjunction with lysine) is to strengthen the walls of blood vessels by creating via collagen. Over time, in a state of even mild vitamin C deficiency, small defects or cracks will appear in the walls of blood vessels, and we developed Lp(a) to fill in those cracks as a type of “sticky” band-aid that will allow the blood vessels to heal. The side effect of using Lp(a) as a band-aid is the delivery of inflammatory inducing cholesterol directly to the arteries.

Later, another researcher, Matthias Rath tested this theory in mice. He was able to turn off the mice’s ability to produce vitamin C, and enable them to produce Lp(a). He discovered that in an environment of both vitamin C deficiency AND elevated levels of Lp(a), plaques would start to form in the arteries, where previously there were none.

Lp(a) has been shown, and is widely accepted, to be a cause of all of the following:

Atherogenesis (formation of plaques)

Coronary Artery Disease

MI

Stroke

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Calcified Aortic Valve Disease

Heart Failure

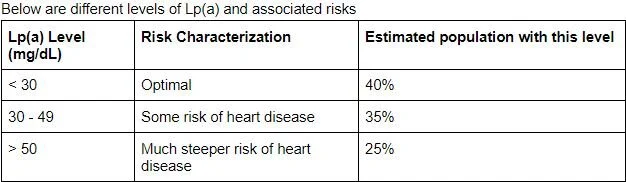

Lp(a) is an underestimated, independent, cardiovascular risk factor. This means that your LDL amounts have no bearing on your Lp(a) amounts. In fact, at any level of LDL, elevated Lp(a) presents a 2 - 3 time higher risk of developing heart disease. The reason this is an underestimated risk factor is because, historically, there has been no specific, effective therapies to lower it. Why diagnose it, if you can’t treat it? Feeding into this fatalistic mentality is the fact that Lp(a) is about 90% genetically determined.

If you have been dealt a bad genetic hand, are you doomed to go bust?

First, you must know what your Lp(a) is. This is not provided by default on a lipid panel, but you can ask for it (and it is inexpensive). Get tested! If you are at risk, you must keep all other CVD risk factors (LDL-c, smoking, etc) as small as possible because you don’t want these more controllable risks to become amplified with Lp(a).

Next, there is some evidence, but not universally accepted or proven to be conflict of interest free, that vitamin C, lysine, and amla (dried Indian gooseberry) can either help bring down Lp(a) levels, or improve conditions where Lp(a) won’t as easily take hold in arterial walls.

Sources

Dr. Joel Khan, MD Cardiologist

Dr. Ford Brewer, MD MPH

Dr. Michael Greger, MD